|

Introduction

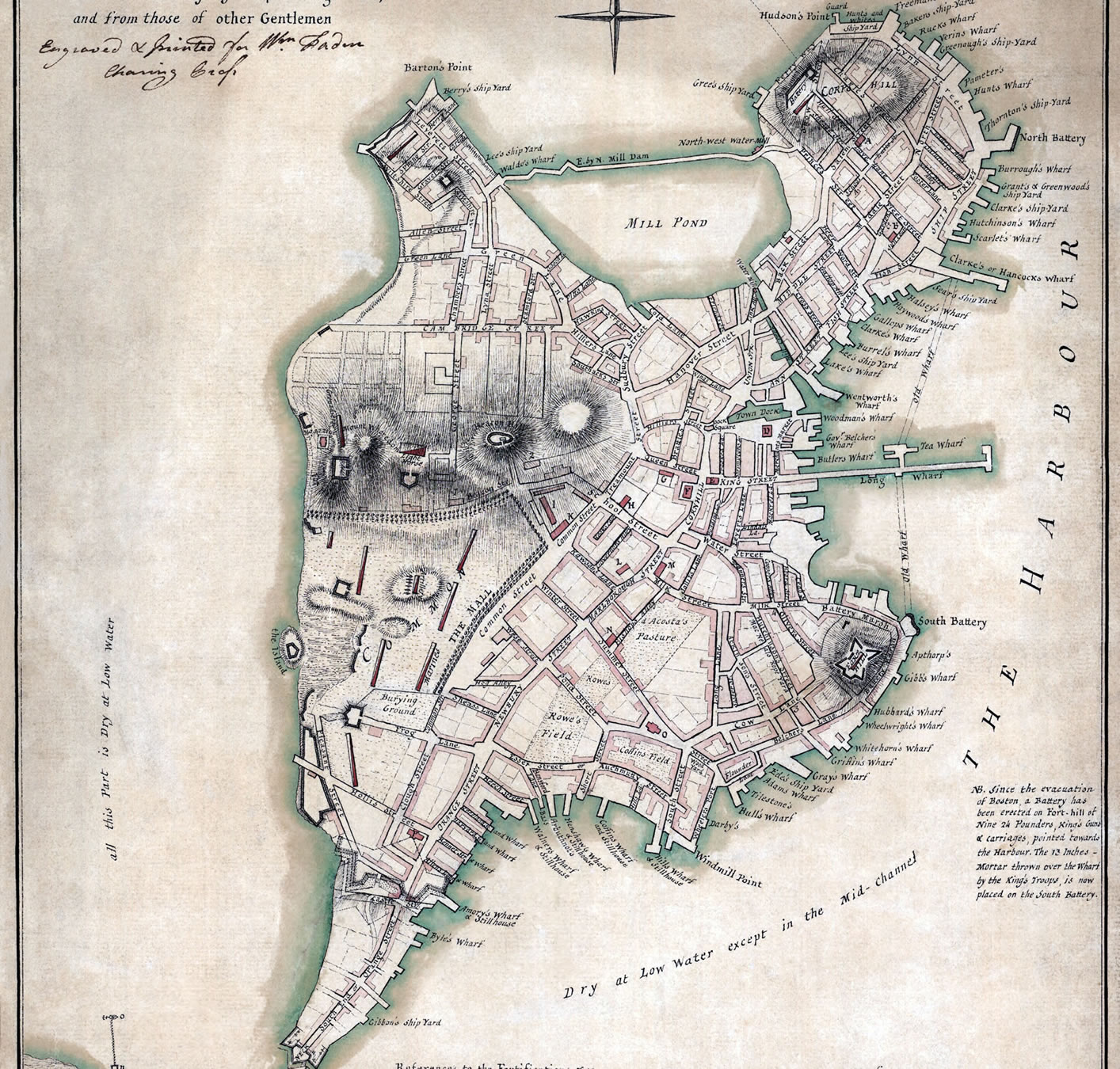

The history of the city of Boston has played a significant role in shaping the development of the Christian Science Center. Early maps of Boston show the area to the west of the Boston Common as part of the Charles River. The expansion of Boston was at its peak in the 19th century when the city defined itself as a central American harbor in international trade relations. Reclamation of marshes, mud flats, and gaps within water bodies resulted in the city tripling its size in less than a century. Particularly, after the Great Boston Fire of 1872, the city better defined its neighborhoods and boundaries after workers were able to further construct the waterfronts and southern part of the city. The Christian Science Center began as the First Church of Christ, Scientist and in later years expanded to become the complex of present day Boston. Its development over the course of a century and the reasons behind its current appearance will be explored by examining its history and various natural processes.

An old map of the town of Boston showing the Charles River to the west of the Boston Common area

photo source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boston,_1775bsmall1.png

|

History of the the Site

Sometime in the mid 1800s when the western boundaries of the Boston Common rested upon the Charles River, the city decided to reclaim the river into what later became the South End and Back Bay neighborhoods. Their decision was mainly due to the need for expansion as stated above and the dry conditions in the surrounding parts of the Charles River. Around the same time, specifically in 1866, famous author and teacher Mary Baker Eddy fell on ice and was bedridden for a month. One day she read passages in the Bible about Jesus’ healing and all of a sudden claimed to have recovered. Word quickly spread of what Mary Baker Eddy later called “Christian Science”, the belief in the power of healing by establishing a spiritual connection with God. I have always found it mind-boggling that a Church of such grandeur and unorthodox beliefs was founded and then granted permission for construction when the population of Boston was mostly Catholic or Protestant. At a time when Irish immigrants and European settlers were making their way into America, it seems bizarre that the city would permit the propagation of such ideas when its growing population rejected them. For that was the case, as Mary Baker Eddy later described that no Christian Church of her day accepted this new set of beliefs and so she was inclined to found her own Church. However, upon examining the social and economic conditions in Boston in the late 19th century, it becomes clearer why Boston would support such a charter. First of all, at a time when the city was gradually establishing itself as a trade hub, it was important to gain as much worldwide recognition as possible. By stating itself as the base of Christian Science, it would become a world pioneer in a field where publications would be distributed internationally, thereby asserting its progressive mindset and willingness to transform from a town into a city. Second of all, at a time when women were still not allowed to vote, this was seen as a step forward in achieving equal civic rights for all as stated in the U.S. Constitution. Finally, the site of the Church had been recently reclaimed and so it is reasonable to assume that the city was eager for developers to take up new projects and begin construction. The First Church of Christ, Scientist was built in 1894 and its domed extension in 1906. In 1934 when taller structures began to rise, the 11 storey Mary Baker Eddy Library was built. As for the present plaza which includes the colonnade, reflecting pool, and splash fountain, it was a part of a larger development project in the 1960s that transformed the site from an institutional zone to a major tourist attraction.

|

|

The First Church of Christ, Scientist built in 1894 |

|

|

Natural Processes

History aside however, nature is perhaps the most powerful and influential driving force behind changes that occur in all environments. The public, and especially policy-makers, play an essential role in envisioning the future of environments. Often they ignore the natural forces that could terminate or accelerate their progress towards shaping the present and future of environments. For nature in all its might, with its air, water, earth, and life is the true mastermind behind the current appearance of environments. It is the orchestrator and enabler of change, and its great power has allowed it to disregard the master plans of architects, planners, and leaders and do as it pleases. The most efficient and sustainable urban environments have come to learn in time that in order to remain prosperous, they must abide by the laws of nature and respect the boundaries it has set for them. Otherwise they suffer nature’s severe punishment and eventually lose their status. Therefore, in attempting to understand urban environment, one must understand the natural processes that have shaped them over time.

The original Church and Domed extension, built 1906

|

Air

The Christian Science Center is currently mostly composed of large open space, the plaza. In the winter, the bare trees fail to protect the pedestrians and people sitting along the benches and ledges from the wind. The buildings play an important role in achieving that, and since they are placed around the plaza, they block wind from several directions. The long colonnade contributes to the wind breaking effect since it prevents air from traveling very long distances at high speeds, and so it minimizes the wind’s effects. In the summer, the big trees provide a canopy that prevents strong winds from attacking the plaza. At the same time allows for a soft breeze to penetrate through into open space to refresh pedestrians, or people who might be sitting along the reflecting pool or playing in the splash fountain. In the alleys between Belvidere Street and the Church, the short narrow streets account for the wind tunnel effect which intensifies the harshness of the cold winds. As for Huntington Avenue, the wide street is lined with trees and buildings on both sides, and so for sidewalk pedestrians the northern and southern winds are easily avoided, yet there is no clear escape from the eastern or western direction. On Massachusetts Avenue, the opposite case occurs where the eastern and western winds are avoided and the northern and southern winds find wide streets to blow through. It is without a doubt that the plaza is better shielded from the effect of strong winds best, yet the air pollution created by traffic is not as easily avoided. While the presence of trees certainly helps offset some of the damage, it cannot be relied on as the sole solution to the problem, since the trees are leafless for half of the year and when they are not, they are in abundance to an aesthetic limit only. So it remains that the problem of air pollution cannot be avoided at a site surrounded by wide avenues that happen to be central to the bustling life of Boston residents.

Long colonade beneath the Mary Eddy Baker Library reduces the effect of strong winds

Rows of leafless trees in the winter bordering the plaza along the sidewalk of Huntington Avenue

|

|

|

Water

As stated earlier, the area over which the site was constructed was essentially a part of the Charles River. Water was slowly reclaimed and soon enough the area surrounding the site was entirely covered in land. Currently there are no natural water bodies that pass through the site or surround it. The closest remains to be the Charles River which within context of Boston’s layout is not directly accessible. One must walk across a few blocks north of Massachusetts Avenue in order to reach the river. Ironically though, water is one of the most attractive features present at the site that draws the attention and admiration of residents and tourists alike. The lack of a natural water body has not prevented the masses from visiting the site thanks to its direct substitute, an artificial water body. Before the 1960s when the site was a strictly institutional area that hosted the First Church of Christ, Scientist and the Mary Eddy Baker Library, it attracted people for a clear purpose. They were either part of the Church’s congregation, or generally interested in finding out more about Christian Science. When the plaza development occurred in the 1960s, the reflecting pool and splash fountain were also built, thereby forming artificial water structures. Perhaps the developers understood that water is an essential element in providing aesthetic value. Most great cities have a water body upon which the city rests or the downtown is centered or the infrastructure is laid out. On a smaller scale, that of a plaza, water “bodies” of sort would be a central aspect of a plaza that is meant to draw people to the site. Perhaps another reason for the inclusion of water in this development is the small size of the Church’s congregation in Boston, and if the site could attract more people, then with proper advertising more people would be inclined to take that first step and explore Christian Science. In the summer, the pool and fountain provide refreshment and entertainment. In the winter however, since the water is pumped from within the pipes and re-circulates to create the “reflecting” effect, it is turned off to avoid pipes from breaking due to water expansion when it freezes. Therefore, while a natural body of water doesn’t formally exists on site, nature once again plays a role in defining the boundaries of artificial water bodies and the extent to which they can be utilized.

Reflecting pool filled with water between April and November,

photo source: http://www.panoramio.com/photo/19046774

|

Earth

The progression of events since the days of reclamation has accelerated to a high level where it seems that the history of the earth on site is almost entirely independent from the present situation. It seems reasonable to assume that when the Church was first built, there were fewer trees planted due to the small size of the site and the lack of proper soil. The land had been previously nonexistent and the reclamation process could only mean that the soil was too brittle and infertile to support large trees growing and extending their roots. As time passed plant seeds from foreign countries were imported into Boston. At the same time, the city was growing bigger and a better sense of awareness of city characteristics was developing. A combination of those factors meant that more greenery was seen around the newly developed land in Boston after the 19th century. When the plaza was developed in the 20th century and the city was quickly becoming an active commercial and financial center, congestion and an overall increase in population and tourists lead to attempts to beautify the city. More parks were developed and on site, trees all along the plaza were planted; they looked good and gave the city an image that promoted a care for the environment despite continued urban growth. Currently there are different types of trees grown in several manners on site. The bigger trees are along the boundaries of the plaza or in rows along the wide sidewalk, whereas the smaller bushes are planted above ground level closer to the pedestrians promoting a sense of intimacy. Also considering that the plaza is mostly large open space bordered by two wide avenues, there is no worry that persists over the amount of sunlight that reaches the trees and plants. For light is abundant when the sun is out, forming a picture-perfect image of a public plaza.

Small bushes lining the southern part of the plaza

Thorny shrubs in the winter

|

|

|

Life

The most impressive aspect of any environment is how nature and life interact with each other to create a homogenous environment. The site clearly went through several changes for over a century, and the development of the plaza as stated earlier was most beneficial in attracting the public to a new place in their city. Walking on site, the most obvious sign of life is animated by its people. In its earlier days before public transport was developed, the site was most easily accessible to the people of the Back Bay and South End neighborhoods which were developed a few years before the Church. Nowadays people visit from all parts of the city and the world and are directly accommodated by the various hotels surrounding the site. They come to worship, to read, to run, to walk, to talk, to think, to relax, to watch other people do these things, and much more. They leave their mark on the lesser known areas on site, on the walls of the allies that intersect Belvidere Street. Their presence and absence is determined by other natural factors, primarily climate. On warmer days the plaza is buzzing with life and in the winter there are very few people. Birds and pets come and go as frequently as people do, and so it happens that when the site is deserted due to unfavorable conditions, there are barely any signs of life, save for the leafless trees. Yet when the people and pet-owners come and the migrant birds return it seems that the site exhibits signs of life again. It’s almost as if life is the true measure of the site’s value governed by nature’s forces.

Graffiti on the doors of deserted buildings in the alleys intersecting Belvidere Street

|

Conclusion: The Big Picture

In each natural process above, a single conclusion can be reached: nature governs all. While environments undergo a variety of changes, their growth and progress is determined by natural elements. In the case of the Christian Science Center, the current site is a result of over a century of knowledge and evolving goals. The site grew with the city within the limitations it was faced with, and over time established itself as an important landmark. The site contributed to the city’s reputation and status in its earlier days of urban development, and later the opposite process occurred when the city’s prominence attracted people primarily and offered them the experience of the Christian Science Plaza. Air, water, earth, and life are the basic elements of nature that propelled the successful collaboration between city and site. They are all intricately related and the removal of any of them would have a negative effect on the site and the city as a whole. There exists a network of relationships between all elements: the people are attracted by water and earth, and the presence of the latter is controlled by the air, which is a result of climate change and all is under nature’s control, and so on and so forth. It remains evident that an urban environment’s greatest ally can also be its greatest enemy. Cities must learn to adapt to the laws of nature and study them carefully in order to develop successfully over time, and the Christian Science Center is a prime example of such action.

water-less splash fountain and reflecting pool in the winter

|

|

|

|

All photos that were not cited were taken by the author.

Other sources used:

"The Granite Garden" by Prof. Anne Whiston Spirn

"Close-Up How to Read the American City" by Grady Clay

|